As an enduring public tribute, parks have long been named and dedicated to outstanding individuals originating from the neighborhoods within which they are located, as well as those with far reaching fame and accomplishments that have positively impacted the community and nation.

Within the New York City counties of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island, are neighborhood parks, playground and stadiums that honor great African Americans by bearing their names.

Highlighted below are thirty of these namesake parks. Kings County, better known as Brooklyn comes in first with thirteen public parks in the outer boroughs featured herein, whose names pay homage to exceptional black citizens. Queens and the Bronx are tied for second, with five African American namesake parks listed, followed by Staten Island, showcasing one.

These "locally" celebrated African Americans have contributed greatly to the city and moreover, our nation as a whole.

West New Brighton’s Corporal Thompson Square was named for Corporal Lawrence Thompson, the first African American from Staten Island to be killed in the Vietnam War. Corporal Thompson enlisted in the Marine Corps and served with the honor guard in Vietnam. Refusing a medical discharge for a foot ailment, Thompson re–enlisted for a second tour of duty and was killed in action in 1967.

Queens

This stadium in Flushing Meadows Corona Park honors tennis player Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr. (1943-1993).

Ashe's first major victory was at the 1968 U.S. Open, when he defeated several competitors to win the men’s singles title. By 1975, he was ranked the number-one tennis player in the U.S. and became the first African American to win the men’s singles at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open.

Named in honor of James A. Bland (1854-1911), a Flushing native who was known as the “world’s greatest minstrel man," Bland Playground is currently located in Flushing.

Bland was a self-taught musician who composed more than 700 songs! He traveled all throughout Europe, from 1882 until 1901, where he enjoyed tremendous popularity and, at the height of his career, he earned over $10,000 a year on tours. He even performed for a number of dignitaries, including Queen Victoria and Prince Edward of Wales.

Sadly, when he returned home to America, his shows were not as popular as they were abroad as vaudeville was the new entertainment style in the U.S. and tragically lost the rights to almost all of his songs. He died alone in Philadelphia. Only later was his genius recognized by music scholars.

The new Louis Armstrong Stadium at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center will debut for this year’s U.S. OpenFlushing Meadows-Corona Park. It is dedicated to the legendary jazz musician Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong (1901–1971), who was also a resident of Corona, Queens from from 1943 until his death in 1971. His home is now The Louis Armstrong House Museum and it is a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark.

Not your ordinary park, the Roy Wilkins Recreation Center, named for the civil rights leader, is an outdoor public space for community entertainment and outdoor enjoyment.

The park is home to a 425-seat theater and its own troupe, the Black Spectrum Theatre, devoted to performing socially-conscious dramas. There is also a four-acre vegetable garden, which gives local kids and adults the opportunity to grow their own produce, which is quite unique in the middle of New York City. Other park features include a year-round indoor pool, outdoor handball, basketball, and tennis courts.

In 1931, Roy Wilkins (1901-1981) began his career with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and rose to the position of NAACP President and was its guiding force from 1955 to 1977. As president, he worked tirelessly to promote voter rights legislation, fair housing laws, and equity in wages. During his tenure he received the Spingard Medal, the highest award given by the NAACP. From 1934 through 1949, Wilkins also served as editor of The Crisis, a magazine founded by W.E.B. Dubois. Upon Wilkins’s death in 1981, President Ronald Reagan called for American flags to be flown at half-mast.

This triangle honors Queens resident Bernard Adolph Tepper (1925–1966), one of twelve New York City firemen killed fighting a blaze on 23rd Street and Broadway in Manhattan on October 18, 1966.

Tepper joined the New York City Fire Department in 1955. He was was actively involved with his community, serving as a Cub Scout Coordinator from 1959–62, as a member of the United Civic Association of Baisley Park, Queens, and on the Executive Board of the Parents Association of P.S. 131 in Queens. The park was named for Bernard Tepper on April 14, 1967.

Bronx

Charlton Garden in the Morrisania section of the Bronx honors the heroism of Korean War hero Sergeant Cornelius H. Charlton (1929-1951) who was awarded a Purple Heart and the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously for his actions in battle. When his platoon commander was seriously wounded during an assault, Charlton assumed command of the platoon, rallied the men, and re-launched the attack. Although his platoon suffered heavy casualties, he launched a second and third attack until the enemy position was completely destroyed.

Charlton received both awards while the American military was still partially segregated, and was barred from burial in Arlington National Cemetery because he was African American. In 1989, the Medal of Honor Society located and exhumed Charlton’s grave and re-interred his remains in the American Legion Cemetery in Beckley, West Virginia to rightly honor him.

Within Grant Park in the South Bronx, is a lovely bird sanctuary named in honor of Dred Scott, the slave who sued for his and his family's freedom in the famous Dred Scott v. Sanford case of 1857.

In the trial, that became known as the "Dred Scott Decision", Dred Scott argued that he should be granted his freedom because he lived with his owner in Illinois and territories where slavery was illegal before returning to the slave state of Missouri. Although he lost his case in Missouri state court, his lawyers appealed it to the United States Supreme Court.

The outcome was rather interesting, to say the least - the court found that no black person, free or enslaved, could claim United States citizenship; therefore, Scott was unable to petition the federal court for his freedom. The court also ruled that Scott's travel to free states did not qualify him to become free.

As a result of the court's decision, outrage was sparked in the North and had a powerful influence on Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party and election, the secession of the South from the Union, and the Civil War. Dred Scott and his family became free, through their new owners, on May 26, 1857. Scott died four months later.

Formerly known as Rocks and Roots Park, the park was named after Estella Diggs, the first African-American woman to represent the Bronx in the New York State Assembly. Born on April 21, 1916, in St. Louis, Missouri, Ms. Diggs attended Pace College, City College of New York and New York University and was in the real estate and catering businesses and a career counselor.

She served as a member of the New York State Assembly from 1973 to 1980, representing the Morrisania section of the Bronx. Her accomplishments include writing more than 70 bills and was responsible for the first Women's, Infants, and Children's program in the state and the first sobering-up station in the Bronx. Estella Diggs Park was dedicated on November 7, 2011.

A 400-meter track & multipurpose field comprise this public outdoor facility in Macombs Dam Park, is named for Joseph Yancey, Jr. (1910-1991), co-founded the New York Pioneer Track and Field Club. The club was founded in 1936 as an interracial track team, which nurtured many Olympic athletes, and was the first of its kind in the United States.

Yancey, who grew up in Harlem, served as a Captain in the Army in the 369th regiment and was the head coach of the Jamaican Olympic team at the 1948, 1952, and 1956 Olympics. His 1952 group included the “Flying Quartet,” a relay team that ran the 1,600 meter race in 3 minutes and 3.9 seconds, thereby winning the gold medal in world-record time. He also worked with Olympic teams from the Bahamas, British Guiana (now Guyana), and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Yancey’s many lifetime awards and honors included induction into the Black Athletes Hall of Fame and the National Track and Field Hall of Fame.

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968) was a pivotal figure in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. In 1963, he organized the March on Washington to support proposed civil rights legislation. There he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The following year, at age 35, King became the youngest man, the second American, and the third black man to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968. One of the great American heroes of the 20th century, he devoted his life to fostering tolerance and equality on the ground that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” His courage continues to inspire people all over the world. King is honored with a national holiday on the third Monday in January, which falls close to or on his birthday, January 15th.

Brooklyn

Benjamin Banneker’s (1731-1806) accomplishments spanned many scientific disciplines. His understanding of physics led him to predict solar eclipses, including the eclipse of 1789. He published the Almanac from 1791 to 1802, which was the first scientific journal produced by an African American. Banneker helped survey Washington D.C. with George Ellicott and Pierre L’Enfant, the French architect who designed the original plan for the nation’s capitol.

This playground is named for Crispus Attucks (c. 1723-1770), an African American killed in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Although little is known about Attucks's early life, he is remembered as a runaway slave from Framingham, Massachusetts, who spent more than 20 years working on ships sailing from Boston.

In 1768, following colonial protests over the passage of a series of import duties known as the Townsend Acts (1767), British troops were sent to Boston to keep order. The soldiers’ presence, however, only exacerbated tensions between the British and the Americans. On March 5, 1770, Attucks joined a crowd that was jeering at British soldiers stationed in Boston. Panicked, the soldiers fired into the crowd, killing five men and wounding two others. Attucks, standing toward the front of the crowd, was the first killed.

The soldiers involved stood trial but were acquitted, and the Boston Massacre became a rallying cry for radical American patriots who used the incident to sharpen the divide between the British and the Americans. Attucks, the runaway slave whose freedom was always uncertain, became a symbol of the American colonial fight for freedom.

The basketball courts at Crispus Attucks Playground are named for world-renowned rapper Christopher "Biggie" Wallace, who lived a few blocks away on St. James Place and played basketball on these courts.

In Brownsville, Green Playground honors New York City’s first African-American Chancellor of the Board of Education, Dr. Richard E. Green (1936-1989). Dr. Green received his appointment from Mayor Edward Koch in March, 1988. His term was cut short when he died of a severe asthma attack in May, 1989.

As Chancellor, Dr. Green cited four main objectives: creating a legislative package to fund new schools, reforming the election process for school board members, giving teachers more say in decision-making processes, and making schools safer and more effective. Dr. Green adamantly believed that children should be "the center" of American culture.

Ronald Edmonds (1935-1983) was appointed senior assistant for instruction under New York City Schools Chancellor Frank J. Macchiarola in 1978, where he served for three years. He initiated the School Improvement Project, which focused on discipline and management. He believed that improving schools for the poorest children would raise the performance of all children. At a time when many educators questioned the validity of testing, Edmonds felt that standardized reading and math tests gave students important information about their performance and indicated to educators and administrators the quality of the education being offered at the school.

In addition to his lasting influence on city schools, Edmonds wrote two books, The Negro in American History (1955) and Black Colleges in America (1978).

This playground in Prospect Park is named for Detective Dillon Stewart, a police officer who was killed in the line of duty on November 28, 2005. Stewart immigrated from Jamaica at age nine and grew up in East Flatbush. He graduated from Lafayette High School and Baruch College. Prior to serving as an officer, Stewart worked as an accountant at the public radio station WNYC. At age 30, he changed careers and quickly earned his reputation as a dedicated officer with multiple commendations for bravery.

On November 28, 2005, the 35-year-old Stewart was fatally shot after conducting a routine traffic stop. He was posthumously awarded the New York City Police Department Medal of Honor on June 15, 2006. Detective Dillon Stewart Playground serves as a lasting memorial to his heroism.

El-Shabazz Playground is named for the civil rights leader El-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz (1925-1965), also known as Malcolm X. Malcolm, whose father was brutally slain by the a Klan-like organization called the Black Legionaries, was inspired by the Elijah Muhammad’s teachings while imprisoned for burglary from 1946-1952. Elijah Muhammad taught that blacks should separate themselves from white society. Only by themselves, Elijah Muhammad taught, could blacks overcome their problems in America. Malcolm started using name Malcolm X (the X meant to signify a lost identity stolen by white oppressors).

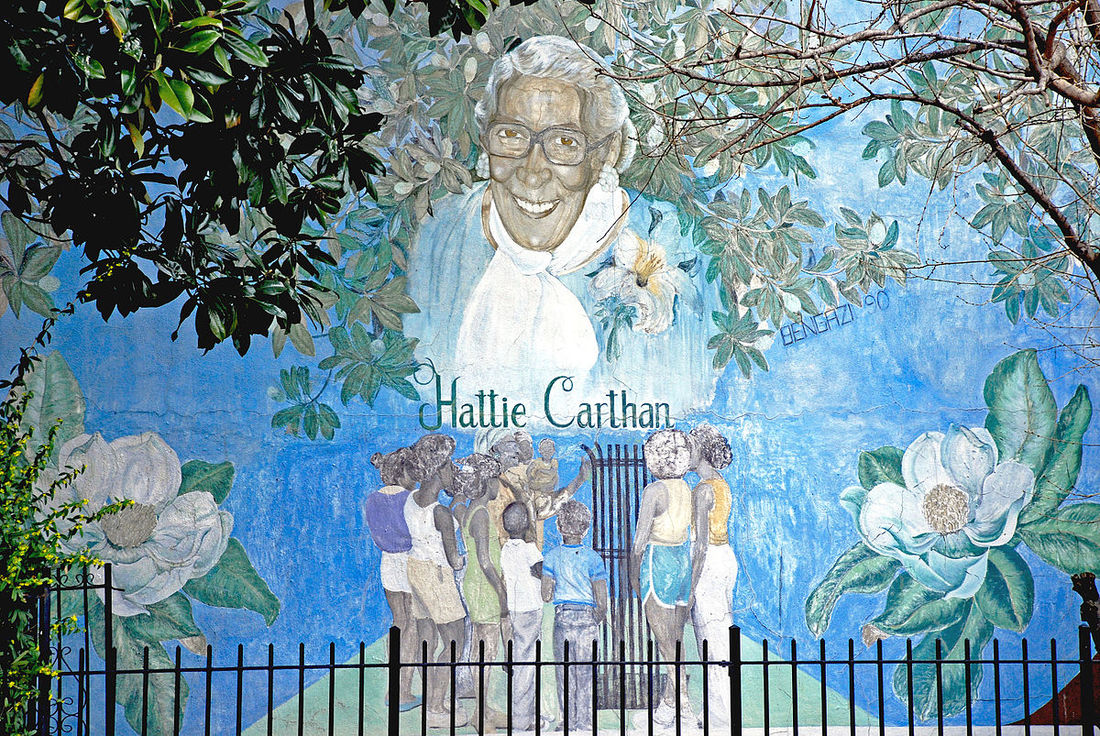

Hattie Carthan (1900–1984) was a Bedford-Stuyvesant resident who always had an interest in trees. When she noticed conditions in her neighborhood beginning to deteriorate, Mrs. Carthan began replanting trees there, and in the process, helped found the Bedford-Stuyvesant Neighborhood Tree Corps and the Green Guerillas.

Carthan also led the charge to preserve a particular Southern magnolia tree (Magnolia grandiflora) that became a symbol of the neighborhood. The tree, rare in the northeast, was brought on a ship from North Carolina in 1885. Carthan not only succeeded in having a wall built to protect this tree but also spearheaded the successful attempt to designate it an official city landmark in 1970. It is one of only two trees to be designated as such (and after the 1998 death of the Weeping beech in Queens, the only tree still standing).

Carthan continued her campaign by convincing the City to convert three nearby abandoned homes into the Magnolia Tree Earth Center. The brownstones on Lafayette and Marcy Avenues behind Hattie Carthan Garden date to the 1880s and now feature a mural depicting Mrs. Carthan. The Center gained not-for-profit status in 1972. In 1998, Parks named the site to honor Carthan.

Herbert Von King Park

Affectionately called the "Mayor of Bed-Stuy", Herbert Von King (1912-1984) is well known for his active role in the community for more than 50 years. At age 20, he founded Boy Scout Troop 219 and later received scouting's highest achievement, the Vigil Honor, for his efforts.

He went on to serve as a member of the the local community board, the Community Theatre Guild, the Bedford Stuyvesant Boxing Association, the Magnolia Tree Center, and more. Von King was the Vice President and Program Director of the NAACP, Brooklyn Branch and was named the first Police Civilian Community Coordinator by the New York City Police Department. In 1983, he received awards from the State Senate, City Council, and 81st police precinct in recognition of his community service. Herbert Von King Park was formerly named Tompkins Park; in 1985, the park was renamed for Von King.

In the early 20th century Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950) became the first African-American editor of the Harvard Law Review. Seven years after receiving his law degree from Harvard, he helped transform Howard University into a full-time, accredited law school as vice-dean. He served as the first ever full-time special counsel to the NAACP from 1935 to 1940 and played key roles in advocating for education equality and eliminating racial discrimination in the hiring process.

This park dates back to 1877, and was formerly known as Underhill Gore. It was renamed by the City Council for Rev. Benjamin Lowry in 1982. Reverend Benjamin James Lowry (1891-198Α) was the long-time pastor of Zion Baptist Church, located at 523 Washington Avenue in the Prospect Heights section of Brooklyn.

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968) - Civil Rights Leader and Nobel Prize winner.

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm (1924–2005), was an educator, social rights advocate and celebrated politician and the first African-American woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

She was also the first major party African-American candidate to run for President of the United States. Chisholm was born on November 30, 1924 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. She was a child of Caribbean immigrants from British Guiana (now Guyana) and Barbados. She later attended Brooklyn College and earned a Master’s Degree in Elementary Education from Columbia University while teaching nursery school. Chisholm became an authority on early education and child welfare. She taught remedial education at 1078 Park Place. Local residents recall Chisholm regularly holding classes in Brower Park during temperate weather. This section of Park Place now bears her name, “Shirley Chisholm Place.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed