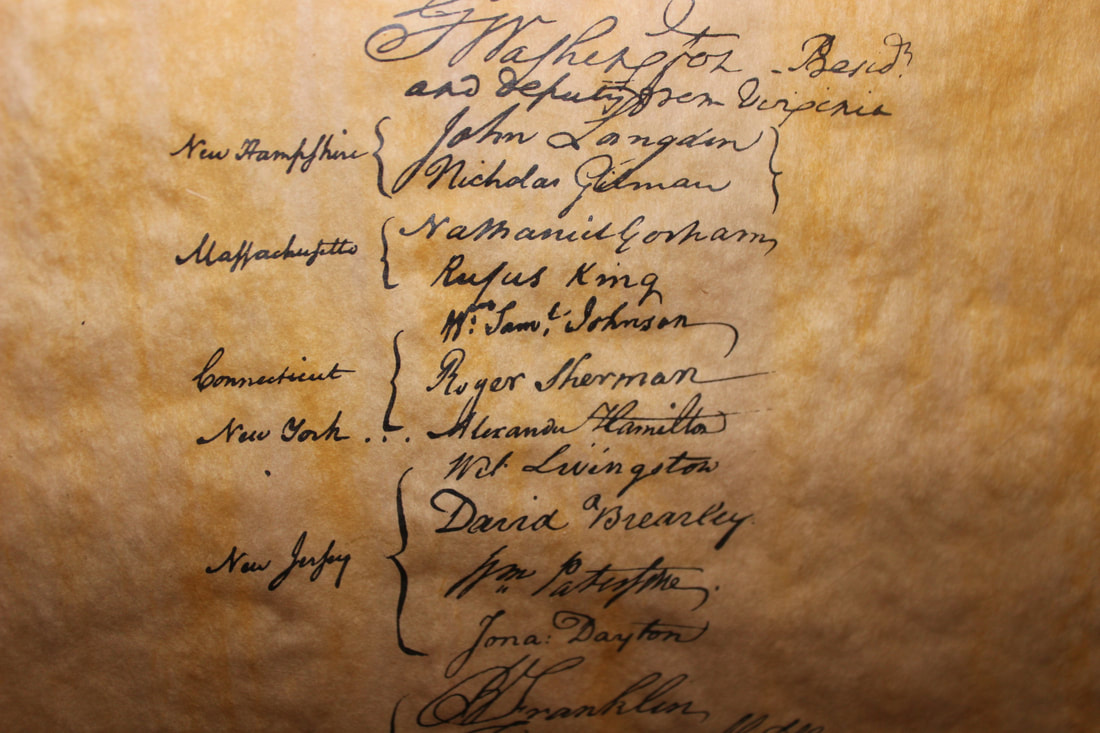

What many of you may not know is that Rufus King was one of the framers of the United States Constitution. As a delegate from Massachusetts to the Constitutional Convention, King's signature appears on the document with other more well known signers that include George Washington, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton.

Rufus King (photo credit: King Manor.org)

Rufus King (photo credit: King Manor.org) I HAVE YET TO LEARN THAT ONE MAN CAN MAKE A SLAVE OF ANOTHER. IF ONE MAN CANNOT DO SO, NO NUMBER OF INDIVIDUALS CAN HAVE ANY BETTER RIGHT TO DO IT.

– RUFUS KING, FEBRUARY 11, 1820

John Alsop King, eldest son of Rufus King - served as the twenty-second Governor of New York in 1857-1858 (photo credit: kingmanor.org)

John Alsop King, eldest son of Rufus King - served as the twenty-second Governor of New York in 1857-1858 (photo credit: kingmanor.org) Within a short period of time after relocating to New York City, King was elected to represent New York in the United States Senate in 1789, remaining in office until 1796.

Rufus King would also be appointed as United States Ambassador to Great Britain under President George Washington.

King and Hamilton were aligned politically as Federalists, and their relationship was bonded closer still as Hamilton was King's eldest son, John Alsop King's godfather!

At the entrance of King Manor - the residence of the King family from 1805-1896. (c) travelincousins.com

At the entrance of King Manor - the residence of the King family from 1805-1896. (c) travelincousins.com So, how did this Manhattan resident end up in Jamaica, Queens? A number of factors contributed to King's purchasing 120 acres in this growing "country" town back in 1805.

While serving as U.S. Ambassador to England for seven years, King became accustomed to living in both the city and the country. Upon his return to America, he decided to create a similar lifestyle and chose Jamaica as the location of his country estate.

The aesthetics of the new abode were not as important to King as were the other opportunities it offered, such as open space, access to church and schools and the health benefits of having some distance from the political world of Manhattan, which come through in a letter written by Rufus King to his sons John A. King and Charles King on November 24, 1805:

"It is about 12 miles from town at Jamaica, L.I. The house is not fashionable, but convenient, the outhouse good, and the grounds consisting of about 50 acres, sufficient to give me pasture for my Cows and hay for my Horses."[1]

King Manor (c) travelincousins.com

King Manor (c) travelincousins.com There were also two major additions to the house itself made by King that resulted in enlarging it to its current size.

In 1806, the first addition, a kitchen, was constructed. This kitchen was built from King’s own lumber and finished with shingles purchased from a neighbor. A few years later, King enlarged the dining room and altered the bedrooms above.

Rufus King along with his wife Mary Alsop King, their five children and paid servants would also expand the property to over 150 acres, improve the land and transform it into a working farm.

Learning about this historic landmark could not be separated from garnering an understanding of Rufus King the man, who was both a practical and down to earth man, with no airs. For example, in the dining room, King had a curved wall built, which was a fashionable architectural feature at the time, adding a lovely and upscale look, but also enabled amazing acoustics, (which I can attest to, having had a first-hand experience within the room.)

In an effort not to show off to his community, the room's curve was designed only to be visible from the interior of the home, and was constructed from the outside to look squared off, resembling other homes in the neighborhood.

King was also intent on being economical and practical in his decorating and furnishings, giving the appearance of wood paneled walls by using less expensive finishes.

Three of the rooms on the first floor are designated interior historic landmarks. These include the Parlor, the Dining Room and the Library.

King was an avid collector of books and amassed a collection of more than 3000, most of which currently reside at the Historical Society of New York, for which he was one of the founders.

Within the library of the home, on a period desk, is a photocopy of an original letter hand written by Rufus King, which was very cool to actually see his handwriting!

Rufus King died in 1827, and at that time, his eldest son, John Alsop King purchased the house and farm, following in his father's footsteps as a career politician. The estate remained in the family until John King's daughter Cornelia died in 1896.

A big part of Rufus and his son, John King's contribution to our country, was their long history of opposition to the expansion of slavery and the slave trade. As a congressman, Rufus King added important provisions to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which barred the extension of slavery into the Northwest Territory.

In 1817, he supported Senate action to abolish the domestic slave trade and, in 1819, spoke strongly for the antislavery amendment to the Missouri statehood bill. In that same year, his arguments were political, economic, and humanitarian; that the extension of slavery would adversely affect the security of the principles of freedom and liberty.

John Alsop King was active, like his father before him, in politics and was also opposed to slavery. In both the New York State Assembly and Senate, he was outspoken about his anti-slavery position and specifically the 1840 "gag rule" which existed to stop the receipt of abolitionist petitions to Congress.

As a congressman, he established an anti-slavery reputation and opposed connecting the admission of free states to the Union with that of slave states. This position continued as Governor of New York from 1857-1859, where he fought for the arrest of “Blackbirders,” which were men who seized free black New Yorkers and sold them into slavery.

Strolling about the residential home first owned by Rufus King and his wife Mary, and later by that of their eldest son, John, was an illuminating experience, as I learned so much about these Queens residents who made quite a mark on the fabric our nation, but seemed to be quite unaffected in their accomplishments.

From the insight bestowed upon us by Ms. Allen, our guide, it appeared that this family's political views were very much in line with their kind values as human beings from the many anecdotal stories she shared and their public position against slavery.

Rufus King Park currently comprises 11 acres, fenced in and housing King Manor. It served as the King family residence from 1805-1896. In 1896, at the time of John King's daughter, Cornelia's death, the Village of Jamaica bought the house and the remaining 11.5 acres, that would become Rufus King Park. In 1905, King Manor opened to the public as a museum.

King Manor was designated a historic landmark in 1966, with portions of the interior designated in 1976 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

With approximately 10,000 visitors annually, King Manor serves a largely minority and immigrant community and engages its audiences through historic site tours, interactive exhibits, lectures, public programs, and school and community outreach. Collections management, preservation, and architectural, archaeological and historical research are continuous activities at the museum. The museum houses a charming piano dating back to the 1800's originating from London, used during musical concerts in the old "parlor."

A beautiful sanctuary in the middle of a now bustling city, Rufus King Park and King Manor reminds us of early days when Jamaica was a young village and our nation was in its infancy. A must-see in Queens!

-E

1. Rufus King to John A. King and Charles King, November 24, 1805, Rufus King Papers, New-York Historical Society (from king manor.org)

For Your Reference:

King Manor Museum

King Park

153 Street & Jamaica Avenue

Jamaica, Queens, NY

(718) 206-0545

Email: [email protected]

www.kingmanor.org

Easy access from:

Long Island Rail Road and Subway Lines E and F

RSS Feed

RSS Feed